Research Help

WHAT TO DO BEFORE YOU GO TO AN ARCHIVES

FINDING PRIMARY SOURCE MATERIALS

First, before you go to an archives, do some preliminary searching on the BMRC Archives Portal for your topic area. If you’ve narrowed your subject, you might want to make it a little broader to get some solid context for your research and to discover related people, events, places, or organizations. Keep a list of these and of other Indexed Topics that you might want to follow later. Look at finding aids for collections that seem interesting and related to your research. Be prepared with basic background information and make note of anything that might help you connect the dots.

If you’ve never used a finding aid before or need a refresher, this video from CU Boulder Libraries gives a great breakdown of the different parts of a finding aid and how to use them.

CU Boulder Libraries YouTube video explaining finding aids.

Highlight and list information about collections you think have the most relevance to your work. Record the title and any identifying number or ID for the materials. If you’re mainly interested in a particular series or set of materials in a collection, note the series or box number and description/title. You will use this information to request materials when you’re at the archival reading room.

AT THE READING ROOM

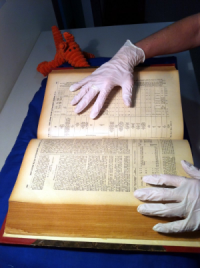

An archival reading room runs differently than a library. Archivists and archival reference librarians will get the materials for you and bring them to your table. Keep everything in the file folder and boxes in the order in which it was given to you and handle the materials with care. Sometimes you will be given white gloves to avoid getting your fingerprints or invisible dirt on the photos or documents.

Finally, always ask your human! Sometimes talking about your project with the archivist or reference person will lead you to new collections –it’s impossible to make all the connections in the finding aid database. Many of the connected dots are in the archivist’s head. Humans are great at finding things and re-sorting the information to reveal new ideas and places to look, and archivists and librarians love to help get the right materials to you, so you can make new discoveries.

If we don’t have expertise in your area, we may know someone to ask; we can usually get you pointed in the right direction. For more advanced scholars, we can recommend a freelance researcher for you.

PLAN YOUR VISIT

Don’t skip learning about the repository you’ll be visiting. Though there are common features and policies, many aspects will vary. You particularly want to make sure it will be open for research when you get there! Check COVID-related policies and other need-to-know facts.

Some repositories require that you email in advance of your visit. Even if it’s not required, it makes things more convenient for you and the archivists if you email the repository at least a few days ahead to say what collections or boxes you’d like to look at. That way they can get materials ready for you in advance.

WHAT TO BRING

Bring your phone, a laptop or other device, paper, and pencils. Yes, pencils, not pens! You’d be surprised at how easy it is to make marks on papers by mistake, especially when you’re trying not to. Even archivists have to be careful. You may only be able to use paper and pencils that are provided for you, and need to leave your things in a locker, so brush up on those handwriting skills. Many reading rooms DO allow laptops and tablets for notetaking, however. (You may wish to find that out before you go.)

Your phone can be a great way to record notes and remember what you’ve seen . . . BUT always ask first whether taking photos of the materials is allowed. You may need to sign a waiver about using them within the guidelines of the archives. Of course, you will need to turn off the sound on your phone during your visit.

You definitely CAN’T bring food and water into the archives, so it’s important to make sure you’re well fed and hydrated before you go! Researching can be exciting and fulfilling, but it’s also often physically and mentally tiring — you’ll be taking in a lot of information which may or may not be relevant to your project.

For some topics, materials may be depressing or personally painful to go through. While there aren’t straightforward ways to prepare for many emotional effects of some archives, it can help to be aware of what you’re getting into. Never be afraid to take breaks when you need them.

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

Once you’re looking at materials the most important thing is (of course) to take notes! Everybody has different notetaking styles and techniques, so do whatever you know works best for you. But since archives have so much material that you can only access there, it may be worth taking notes of things you might not write down in other settings.

If something connects to something else you read or experienced, write it down, even if it doesn’t seem that amazing or relevant in the moment. Did you skip a box that has related materials? Noting that could be useful if you need to go back for further research! You should also take notes with information you’ll need to cite your sources later, like box and folder numbers, collection names, and other details.

INTERPRETING WHAT YOU’VE FOUND

Primary sources are different from secondary sources and require you to do things differently. With journal and newspaper articles, and books, you gather varying viewpoints and information and put it together to analyze and clarify the author’s ideas. With archival materials, YOU provide the perspective to make sense of things and flesh out a topic. You may need to think like a detective, reading between the lines of correspondence, or speeches, ferreting out facts from individual descriptions and newspaper accounts. Listening to an oral history, what stands out? What was important to that person, and what didn’t they talk about (that someone else did)? Take advantage of your interrogatives to dig deeper: the who, what, why, where, when, and how.

One of many basic mnemonic frameworks to think through the meanings of your sources is SOAPS:

- Subject - What is it talking about?

- Occasion - When and where was this record created or found?

- Audience - Who is it for?

- Purpose - Why was it created? Why do I care?

- Speaker - Who is speaking or who created it?

You can also check out this helpful resource from University of Maryland Libraries that breaks down SOAPS and some example interpretations of different kinds of primary source documents, like newspapers, photographs, electronic records, and more. These examples show the types of context you might need to search for while using primary documents, and some tools to do so.

FURTHER RESOURCES

There are so many more great tips that have been compiled by archivists and researchers, here are some we’ve found helpful!

- For a guide on citing primary sources in both Chicago and MLA styles, check out this page from the Library of Congress.

- See the sidebar for a couple of great zines for getting started in archives.

- Advice on taking notes from the University of Toronto's Writing Advice page.

- For some advice and personal reflections that may be relevant for graduate students or others embarking on more intense research processes, see this blog post by Stuart Schrader

- For more in-depth advice on choosing a research topic, see MIT’s overview here.

Moving and Handling Archives – The Basics (nsw.gov.au) Photo credit for image of white gloves, hands, and old book.

Photo of Opening Day at the George Cleveland Hall Branch, 1932. Photo 084 in the George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, Chicago Public Library, Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Woodson Regional.

"What is a Finding Aid?" video created by CU Boulder Libraries: “this video is a deep dive into understanding finding aids, the documents created to describe archival collections.” CC BY 4.0 license: Creative Commons —Attribution 4.0 International —CC BY 4.0